The author of this article, Henk den Haan, is the initiator of the Organ Attics project, one of the enthusiastic guides, a Rotterdammer and an eyewitness. Henk was 6 years old when the Second World War began.

10 – 14 May 1940

“Henk, come quickly and look”. My father awakened me with these words at around six o’clock on the morning of Friday the 10th of May 1940. He was standing at the window in his bedroom, looking out. I could not believe what I saw and heard… the loud droning of tens of low-flying German airplanes flying westwards. No, not to England, as was thought, but to the Waalhaven airport, which had already been bombed heavily and was being reconstructed and prepared for more landing capacity.

We lived in Rotterdam South on the Groenezoom in Tuindorp Vreewijk, close to the Zuiderziekenhuis (hospital in Rotterdam South). I was a six-year-old boy and went outside frequently to play with friends, but also to go to our primary school on the Mare.

One day I saw Dutch soldiers standing there; I recognized them from Spes Bona, a dance hall on the Enk, which, since the mobilisation, was being used as a barrack. They were walking away. Later we heard that they were fleeing. They had lost a fire fight with German soldiers in the Zuiderziekenhuis. The Germans commandeered the Zuiderziekenhuis, because they had many wounded after the landings at Waalhaven airport. In fact, there were so many wounded that they had to send the Dutch patients to the nearby Breeplein Church and the Vredes Church. The pews were removed to make room for beds and mattresses.

Reverend Brillenburg Wurth’s wife was a nurse and thus helped with the patients. They were also asking for donations of bandages and other items from the neighbourhood. My mother had a one-year-old baby and donated the crib with nappies. But there was more happening; several fights were breaking out and everyone was scared. The hospital was occupied by the enemy. Feyenoord Stadium in Rotterdam South was being bombed. That was so close to the Breeplein Church with all those patients, that the church members painted, with big brushes, red crosses on white backgrounds on the huge roof of the church and on the rectory on the Randweg. They also painted HOSPITAL in big white letters on the side wall of the church. The faded crosses and letters are still visible today.

Friend or enemy?

The battle for Rotterdam lasted five days. The riverfront of the Maas was defended heroically; the German advance was stalled, to the annoyance of Air Marshall Göring. Since the big bridges at Moerdijk and Dordrecht were still intact, large armoured divisions with tanks rolled into Rotterdam. On the 14th of May they also entered Rotterdam South. The tank soldiers sought shade under the trees on the Groenezoom, fairly close to our house. Then something strange happened: the German soldiers came out of the tanks and sought contact with the residents. They asked for water and wanted to use the toilets. In a friendly voice, they called us Dutch their brethren, thus also Germans…This battle is not with you, but against England, they said. I also saw our neighbours talk to them. Strangely enough, our neighbours believed them. Rotterdammers were not anti-German, on the contrary. We earned our living from the transit trade with our hinterland. And did the Germans not have the best cars, composers, philosophers and other scientists, all terribly “gründlich” (= solid) In addition, the Boer wars were still fresh in the memory of a lot of Rotterdammers, the wars in which the English had introduced concentration camps.

An enemy after all

That the fear of bombardment was realistic was made clear four days later when the German Air Force razed the whole city centre of Rotterdam to the ground. That was on the 14th of May. I still remember half-burned pieces of paper raining on our street, carried by the wind from the burning city. It was not only the bombs that destructed the city centre; the fierce winds caused whole streets to burn and due to lack of water supply, the fire brigade could only stand by helplessly.

Hundreds of people died, thousands were wounded and tens of thousands were rendered homeless.

Rebecca’s family was also affected, because the whole Jewish quarter where the Hilton Hotel now stands, was destroyed. Together with 79.000 other Rotterdammers, they were instantly rendered homeless and had to relocate to the Dordtselaan in Rotterdam South.

Persecution with stars

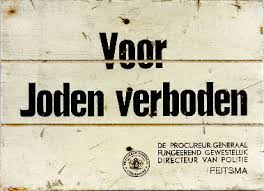

Just as in Germany, the Jews in the Netherlands were fired from official institutions and the persecution began. Increasing numbers of boards with the text “Forbidden for Jews” appeared and anyone who did not obey was arrested. That happened to the Director of the Blijdorp Zoo also. Jews were not allowed on bicycles or on trams, not in the cinemas or in the swimming pools. In 1942 all Jews who went outside had to wear a yellow star with the text “Jood” (Jew). They had to buy these stars themselves using their textile coupon to pay for them.

It became worse when all Jews received an official document from the City Council, addressed by name, street and house number, with the summons to report at 8 p.m. at Loods 24 (Warehouse 24) in the Stieltjesstraat. So-called to go and work in Germany. At the city Council, therefore, they could identify all Jews precisely and know where they lived.

The razzia in Rotterdam

As a child of six, I found this an exciting period. We made weapons and played at war, as children are wont to do. During the war, our family consisted of father, mother and four children. In the winter of the famine, a fifth child, a girl, was born on 5 January 1945. We lived not far from the Hoeksche Waard and my father went there on Saturday afternoons to look for food, like many other Rotterdammers. But the Germans sent them away from the Barendrecht bridge. And then he would return home empty handed.

My father was arrested and taken away in the razzia of the 10th and 11th of November 1944. This was the biggest razzia the German occupiers carried out during the Second World War. More than 50.000 men from Rotterdam and Schiedam, between the age of 17 and 45, were deported to Germany. My father was taken to Ulm, Bavaria. He worked there on the railway line. He was living in a school building in a small village, together with many other convicts. There was enough to eat; they often ate with the families of farmers.

He returned home in June 1945.

Proud of my mother

I was the oldest of the children and was sent out to look for food and firewood. However, everyone was on the lookout for the same things, so the bounty was never large enough. Since the family had extraordinarily little to eat, I was sent in a Rhine barge to the northern provinces in March 1945 with hundreds of other children. I was brought to Nieuwe Pekela, where there was enough food.

It must have been a terrible time for my mother. She had no knowledge of where her husband or her eldest son were, she had a child who was ill, and there was barely anything to eat for her and the other three children. I admire her courage enormously. During that time of war, a special bond developed between us. She lived to be 95 years old and was thus, happily, a part of my life for a long time.

The war continued to haunt me

After the war everyone was involved with reconstruction and no one talked much about those five years. I went to school and picked up my life again. Still, the war continued to haunt me. The 40th anniversary of the liberation was celebrated and commemorated in 1985; as part of the commemoration, my school in Spijkenisse could adopt a monument. Through the City Council of Spijkenisse, I discovered a house in the Voorstraat 14a in Spijkenisse, where the Jewish family Levie, consisting of father Salomon, mother Mina, son Charles and daughter Ellie, had lived. Mina’s aunt Jaantje de Vries had also lived in that house. They were all murdered. Their story is one of a million stories about the Jews, but because this was so close to home, the story of the Levies really touched me enormously. That house is now a Monument.

Postscript: You can read more about Henk den Haan and his involvement in the rediscovery of the hiding places in the Breeplein Church in Rotterdam in the book De Orgelzolders by Anja Matser or in its English version, The Organ Attics.