“Any hint of racism, passive or aggressive, was completely foreign to him”

Leo Lashley’s roots lay in West Africa. The exact location is not known but must have been in one of the areas where the English acquired slaves to labour in their colonies on the other side of the ocean. For example, an ancestor of Leo Lashley was shipped to the English colony of Barbados as a slave labourer, working under inhumane conditions on a sugar cane plantation.

Slavery was abolished throughout the British kingdom in 1834. Leo’s father Francis sought refuge elsewhere: he exchanged the Caribbean Island for British Guiana, a neighbour of Suriname. One day, he crossed the Corantijn River and settled in Suriname, then still a colony of the Netherlands.

Seeking good fortune in New Nickerie

Francis Lashley sought his fortune in Nieuw Nickerie and he succeeded thanks to the trees that Surinamese called the balata or bolletri. At that time, we are talking about the second half of the nineteenth century, thousands of people tried to earn their living by tapping the sap from this special tree. Francis bought their harvest and sold it at a profit to manufacturers of transmission belts, conveyor belts and telegraph cables. He became rich but managed to gamble his fortune away overnight with a game of mah-jong, minimising any prospects for the future of his eleven children.

Graduating and earning money

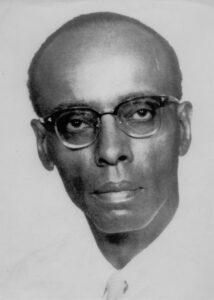

Francis’ son Leo was born on March 24, 1903, in Nieuw Nickerie. The family later moved to the capital Paramaribo. Young Leo knew how reckless his father could be. He saved as much as he could, completing secondary school in Paramaribo and then going on to medical school. The Evangelical Brotherhood (also known as the Moravian Brethren) members, also called Hernhutters, gave him solid support. The members of this denomination helped him achieve his goals of graduating and earning as much money as possible to fund the education of his siblings. One of his sisters became a pharmacist in Paramaribo, a brother became a dentist.

A ‘forgetful’ doctor

The last phase of Leo’s education was in the Netherlands in the 1930s, where he had the opportunity to graduate with Prof. Dr. H.J.M. Weve, professor of ophthalmology in Utrecht. In 1933 he obtained his doctorate in medicine. During one of his internships, he met Adriana Hendrika Helena (Helen) van der Drift, whose father was a general practitioner. They fell in love, married, had three sons (Francis, Jaap and Lenny) and settled on the Randweg in South Rotterdam. The “Negro Doctor” as he was known, quickly became a well-known figure in the city, because he went above and beyond for the well-being of his patients and often “forgot” to bill the poorest and the less fortunate.

Leader of the Doctors’ Resistance

Leo Lashley did not stand by idly during World War II. On the contrary. He became the leader of the doctors’ resistance in Rotterdam, provided shelter to a Scottish pilot whose plane was shot down by the Germans and drove time and again, during the Hunger Winter, to the Hoeksche Waard to get food. Prince Bernhard had charged him with the organisation of the hunger hospitals and with transporting food from the Hoeksche Waard. Leo’s son Jaap was allowed to come along now and then, and he remembers well how exciting it was to tempt the German sentries to let them through. A bottle of gin sometimes helped. Lashley was arrested twice, but released just as many times because, according to Jaap, the Germans could not do without him as an ophthalmologist.

“That he survived this,” he says, “is a miracle of God.”

Ophthalmologist as obstetrician

The very religious Lashley was an elder and therefore a member of the church council of the Breeplein Church in South Rotterdam. As such, he had knowledge of the six Jewish people in hiding in the Organ Attics of that church. He knew that some of the food he picked up was meant for them. Later, he also knew that the youngest person in hiding, 19-year-old Rebecca Kool, was pregnant. The moment he learnt that two other doctors were refusing to assist her during the pregnancy and the birth of her child, he was furious and said, “I’ll do it.” He threw himself into studying from books on obstetrics to ensure he built up adequate knowledge, and, on January 6, 1944, he helped deliver the healthy baby Emanuel Alexander Emile Kool.

Deep disappointment

After peace was restored, Lashley was deeply disappointed with the social and political developments in the Netherlands. He saw how all the people who were supporters of the occupiers during the war, were appointed to senior positions without facing any opposition or obstacles. This was also the case in the Zuiderziekenhuis.

In January 1948, at the request of the Surinamese government, he participated in a conference in The Hague about the future of the Dutch colonies. There he met the representative of the Antillean government, Moises Frumencio da Costa Gomez, later Prime Minister of the Antilles. Da Costa Gomez persuaded Lashley to settle in Curaçao as a government ophthalmologist. That was at the end of 1948.

Flight to Curacao

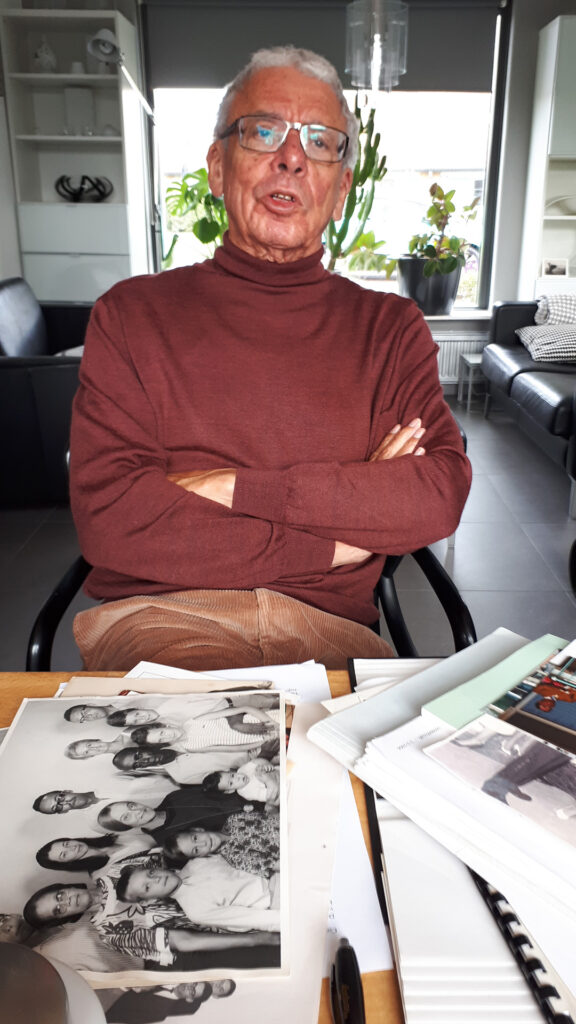

His departure could be seen as a flight from the Netherlands. Jaap Lashley: “My father and I discussed this extensively. Especially around the role played by the future Prime Minister De Quay and his two cronies at the start of the war.”

Jaap Lashley is referring to the Nederlandsche Unie which, in July 1940, only a few weeks after the Germans overran our country and bombed the heart of the city of Rotterdam, issued an appeal to the Dutch people. De Quay and his two companions wanted the people to unite “in work focussed on the preservation and strengthening of the homeland and community, and in preparing for the conditions and means of their existence and well-being in the future.” “My father called it treason,” says Jaap Lashley.

But there was more. Quoting from a report by the Homeland Security Service about Leo Lashley: “Immediately after the liberation he played a very prominent role in establishing the municipal administration here. Being coloured, he would have been forced out of this position to some extent, which grieved him greatly.”

“They literally bullied him out of the organisation. This incident was the last straw; he was completely fed up with the Netherlands,” says son Jaap, “so we went to Curaçao.”

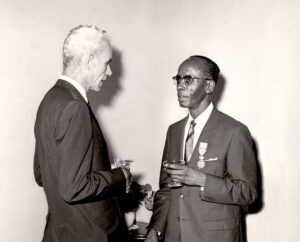

Just like in Rotterdam, Lashley was also socially active in Curaçao. He sat on many executive boards and committees. Sport associations, as also the Cultural Center Curaçao association benefited from his talents. Queen’s Day 1970 was a special one for Leo Lashley: he was appointed Officer in the Order of Orange Nassau.

The end

The marriage with Helen van der Drift ended in 1965, although they were never formally divorced. She settled in Amsterdam where she studied Spanish. In 1977 Leo Lashley returned to the Netherlands, crushed by Parkinson’s disease. Helen cared for him for years. “An act of compassion”, son Jaap calls it. He spent the last months of his life in the Amstelhof nursing home, which now houses the Hermitage Amsterdam Museum. Leo Lashley passed away on August 1, 1980. The Surinamese association JPF (Justitia, Pietas, Fides, or Justice, Love, Loyalty) in Curaçao hung the flag at half-mast for a week.

“A man of blameless integrity”

Dr. Lou Lichtveld (Albert Helman for literature lovers) calls him in In Memoriam ‘A man of blameless integrity’. He also writes: “I do not know if his descendants do it, but I have held him as an role model for myself. Any hint of racism, passive or aggressive, was utterly foreign to him.”

The above text is partly based on interviews with Jaap Lashley, approved by him on October 1, 2021.

(Copyright Organ Attics Foundation Rotterdam)